There are few enough documents that can allow us a glimpse into the personality of an ancestor. A will is certainly one, and even without reading too much into the data, I feel that I know my great-great grandfather much better for having read his.

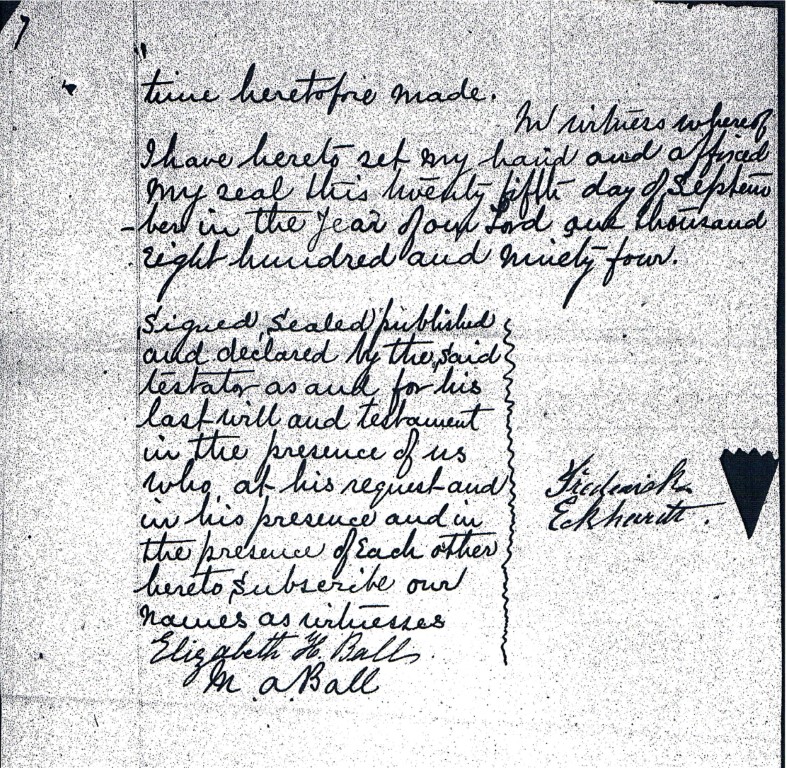

Frederick Eckhardt died on November 11, 1901, aged 82, at his farm property near Campden in the Niagara District. He had prepared his will seven years earlier. In it, he laid out twelve clear and specific directives. The first four give instructions to:

- Pay all outstanding funeral and testamentary expenses.

- “Erect a suitable monument or tombstone at my grave.”

- “Bequeath my family Bible containing verities of births, marriages and deaths in my family” to his son Byron, with “my wish that he carefully preserve it.”

- “Bequeath my Bell organ to my daughter Sarah during her life and at her death it is to go to and become the property of my grand-daughters Edna and Edith, the daughters of my son Byron.”

Here I start to get a measure of the man. I can see someone for whom it is important to be remembered in a tangible way (the “suitable” monument or tombstone.) He is someone who values – even treasures – family and family records. (Note the importance for Frederick is not the Bible per se, but the “verities” contained in it.)

The Bell organ is the only piece of household goods that he highlighted for inheritance. Possibly a status item for him, the organ was clearly important to his unmarried daughter Sarah, who lived with him until her death in 1896. It is also probably safe to assume he had a close relationship to his granddaughters Edna and Edith, and that they valued the organ and/or playing music as much as he seemed to.

The Pragmatic Provider

The remaining directives in the will are all about providing for his children. Frederick and his wife Magdalena (who had died back in 1869) had eleven children in total, only seven of whom survived him. First, he expressly excluded two of his sons, William and Christian, and the heirs of his late son Jacob, from receiving any portion of his estate, “as they are already in comfortable circumstances.”

So: a pragmatist and realist. Clear eyed, or at least firm in his judgements of those close to him and willing to act on what he decided was fair.

Frederick also specified a caveat in providing for his son Solomon (my great-grandfather). Frederick had provided $280 (about $10,000 today) as security for promissory notes taken out by Solomon. Frederick did this “in order to assist him.” He instructed that if the notes had not been repaid by Solomon at the time of Frederick’s death, the sum was to be deducted from the monies payable to Solomon from the estate.

So: a willingness to help out, tempered with tight control on his money, and a strong respect for money owed.

Beneath the Directives: Clues

The probate papers assess Frederick’s estate as $5,083.17, which is about $184,000 today. About half of that was the value of his 51 acres of farmland, atop the Niagara escarpment near Vineland. Frederick willed to his son Byron “and his heirs and assigns forever, all my real estate.” But he also directed that Byron had to pay a total of $2,500 for the property (about $90,000 in today’s dollars) to the executors in yearly payments. The executors would then divide that money into equal shares and pay each of the inheriting children, including Frederick’s late daughter Elizabeth’s children and Byron himself.

A bit of a complicated way to allow Byron to stay on the farm without handing over half of the estate to this one son, plus a way for Frederick to provide financial support using the whole of his estate, to his children who needed it.

So clearly, Frederick considered himself a provider for his family, and acted accordingly in life and in death.

While I think it can be dangerous to assume too much from data, I also think it’s possible to get a glimpse into the nature of a person from the records they leave behind. For this reason, wills and probate records are fabulous sources for genealogists. Beneath the legal language beats the heart of a person who, in addition to directives, leaves clues about their personality and their values.

I found this very interesting and enjoyable to read. It brought memories of my grandparents who lived in Perth, Ontario. I remember how interesting and loving they were when I was 10 years old. I was living on the Alaska highway at Fort Nelson when they died. Never heard of a will. Wish I could read it now just for memories.

I was fascinated by how much personality seemed to be in this will! So glad you enjoyed this and that it sparked some good memories. And if your grandparents did leave a will, it would be held by the Ontario Archives. Maybe something to look into sometime…

Wow, I wish I knew how to get a hold of this type of record from my grandparents. What a find and what insight into someone’s life.

Amazing, isn’t it? I wonder if there’s an equivalent to the Ontario Archives in Holland, where you might explore. Lots of insights to be found!

Hi there, thanks for your suggestion. I will find out thru my brother or sister if this type of info is available to the public.

So, so fascinating. This makes me want to rework my own will – which is a boilerplate, standard legal thing – into something with a little flavour. I feel like it would be a glorious afternoon to just head down to the will archive of Ontario and pick a random year from the last century and sit down and read. The things you’d discover!

Oh, don’t tempt me!! I already have a list of other Eckhardt wills that are on file there, that I noticed from the Index. Can’t wait to find out what I will learn. 🙂

How wonderful! You find the good and make, even, a will interesting. Thanks.

Have a very Merry Christmas!

Love, Susan

Glad you enjoyed the read. Amazing how revealing this type of document can be!

Merry Christmas to you as well, Susan, and to all the Grangers there.