Have you ever thought about where your family members were, and what was happening to them in the year Canada became a nation? As part of my “Canada 150” celebration, I did just that. And although I know a lot about my family history, this was a different point of view, and it brought me some surprises.

At first glance, several families on either side of my lineage seemed to be quite stable in 1867. They were employed, whole, living in established communities. But I soon realized this was not to last. In Canada’s Confederation year, two branches of my family stood at the brink of heart-wrenching catastrophe, and another would see a significant birth. These ancestors’ lives were about to be forever changed, and I can’t help but think of the irony of a bright, new Canada in the face of their stories.

The McSorleys

In 1867, my maternal great-grandfather, Richard McSorley, was three years old. He was living in Buffalo, New York with his Irish-born parents Hugh McSorley and Jane Byron, and his four older siblings. Hugh was working as a horseshoe nailer/blacksmith and also serving in the Navy as a labourer.

By the following year, the family would be completely disintegrated. I’ve been unable to find any documents that tell what happened to Hugh and Jane, but on August 18, 1868, Richard and his brothers Charles and Hewitt would be taken to the Buffalo Orphan Asylum by a neighbour. From there, as each of the boys turned 11, they would be indentured – contracted out for labour – to households in New York State, far apart from each other.

Richard would be taken in by a farming family in Hinsdale, New York, where he would live as an “adopted son” with the new name of Henry R. Scott from 1874 to 1880. This suggests that his situation was better than many other orphan placements, yet a handwritten notation against his indenture record in the orphanage ledger may hint at something else. It says, “Ran away.”

Richard would disappear from the official records for the next 14 years. Of course, in the late 1800s, this was entirely possible to do; according to his daughter, my grandmother Mary, Richard was “riding the rails” across America all that time. He wouldn’t reappear again until 22 May 1894, the date of his marriage in Buffalo to my American-born great-grandmother Josephine Robinson.

For the rest of his life, Richard would continue to wander. A housepainter by trade, he would (as remembered by my grandmother) announce to my great-grandmother Josephine, “I’m going to check on a job,” and be gone for up to six months. When he returned, my grandmother and her brother Arthur would be told by Josephine, “he is to be treated with respect; he is your father.”

Richard would die of a heart attack in Los Angeles, 8 May 1935. At that time, he’d have been a resident there without his wife and children for over 10 years, although he did visit Buffalo occasionally, and Josephine and the children travelled at least once to California.

I wonder what Richard’s life would have been like, what choices he might have made, if his parents and siblings had been able to continue on as they had been in the year of Canada’s Confederation.

The Eckhardts

Meanwhile, in 1867, my paternal great-great grandparents Frederick Eckhardt and Magdalena Honsberger were living on their 50-acre farm atop the Niagara escarpment just east of the village of Campden (near Vineland.) Magdalena’s father, Christian, had arrived in Niagara in 1799 at the age of 18. He was part of the second group of Mennonite families to walk over 600 kilometres from Buck’s County, Pennsylvania to establish homesteads in Niagara.

Frederick had arrived much later, from Germany. His earliest official record in Canada is when he purchased the Niagara farmland in 1844. On this farm he and Magdalena were raising their 10 children, most of whom were still at home on 1 July 1867. Overall, Confederation year seems to have been a good one for the Eckhardts, including the birth of their first grandchild. But like the McSorleys in 1867, this branch of my family was also about to face a tragic blow. Just two years later, Magdalena would die suddenly at the age of 50, leaving Frederick with six children under the age of 15.

Their son Solomon, my paternal great-grandfather, would be only 12 when he lost his mother. Frederick would never remarry; he would live another 32 years and die of a sudden stroke in his blacksmith shop on the farm, in 1901.

Once again, just after a brand new country came into being, members of my family were struggling to continue on with life as best they could.

The Gerencsers (Grangers)

In contrast to these stories, 1867 did not bring tragedy for my other maternal great-grandfather, József Gerencsér. He was born on 19 September in that year, in Kispécz (now Kájarpéc) Hungary, which is about 150 kilometres west of Budapest. The Gerencsér family’s long and difficult road to Canada began in the year of Confederation, with József’s birth. He would grow up to be the ancestor I now thank for bringing his branch of my family to America, and from there – not due to death but a different kind of misfortune – to Canada.

József came from a long line of landless peasants who toiled in poverty on other people’s land, with no opportunity to improve their lot, in a country where land ownership was everything. Luckily, in József’s time, an option arose to the life of the powerless peasant: America. József would come to Buffalo, New York in 1902 at the age of 34, and work for two years in a factory to earn enough money to be able to return to Hungary to fetch his family. In 1905, he would bring my great-grandmother Julianna Molnár and their two sons József and Istvan to the Port of Baltimore and from there to Pennsylvania and finally, to Buffalo. My grandfather Istvan – whose name would be Americanized by a teacher to Stephen Granger – would be seven years old at the time.

Thirty-two years later, in 1937, Stephen would be thrown out of work by the Depression. He would answer a call from a friend for his experience as an international shipping clerk, and thanks to this opportunity, he would bring my grandmother, Mary McSorley, and my eight-year old mother, Mary-Jane, to St. Catharines.

Legacies

One hundred and fifty years after Confederation, Canada is widely accepted as being one of the top 10 countries in the world to live, and I’ll be celebrating. I’ll also be thinking about the ripple effects of birth, death and misfortune on these ancestors of mine. I’ve been saddened to discover family tragedies that happened so close to Canada’s Confederation. Yet I’m also grateful for the family members who made their way to Canada, allowing me to enjoy all this country has to offer. And I’m happy that my roots hold people who, whether born into a life of no opportunity, or thrown off course by death or unemployment, made choices and found what they needed to continue on with life. These are strong legacies.

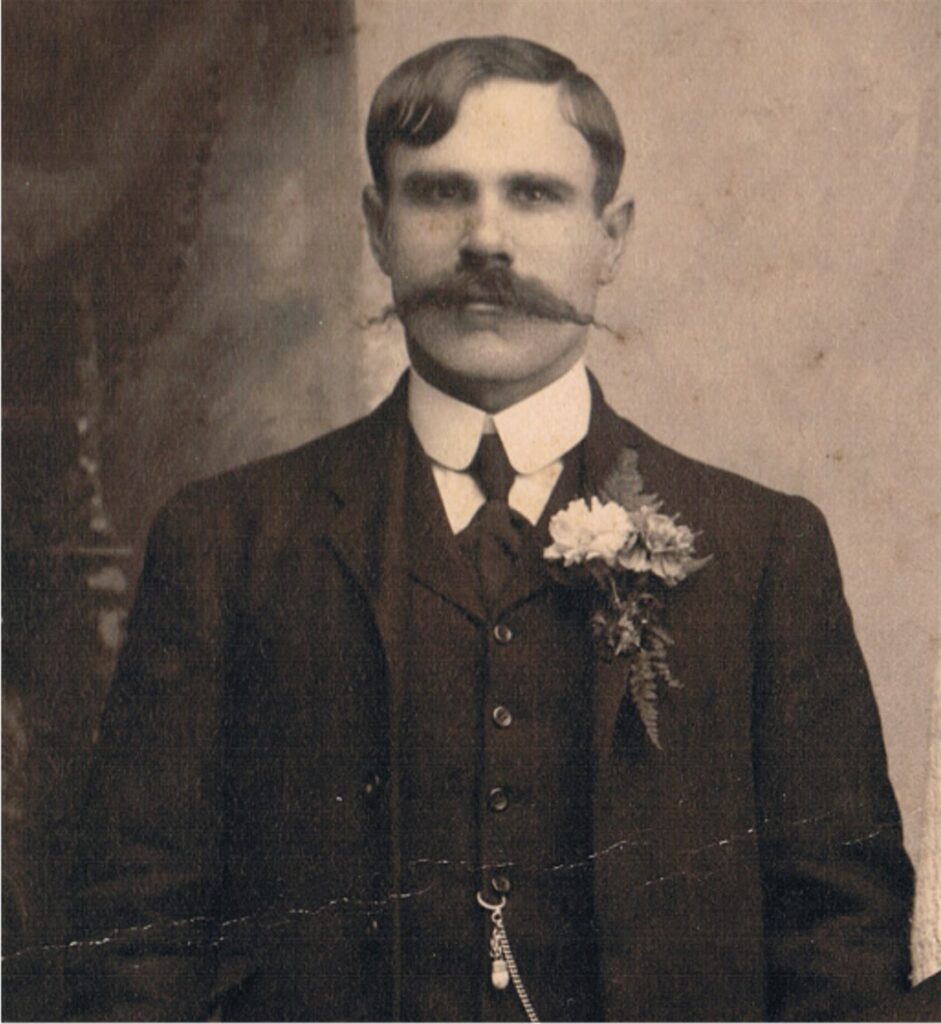

Great piece as usual. Boy can a I see your family resemblance when I look at the picture of your great great grandmother Magdalena Eckhardt. BTW my maternal grandmother’s name was Magedalena too.

Thanks, M2! Glad you liked it. Isn’t it fascinating to stare into these faces and see resemblances? Someday I’d like to do a piece on the women in my lineage.

Love this story – so thought provoking! I’ve never been one to want to explore my family’s history but this piece makes me wonder what my own ancestors were doing in 1867. Hm…