NOW THAT’S A POEM: Where Inspiration Comes From

Have you ever wanted to ask an artist, “Where do you get your ideas?” I’m here to help! As many of you know, I’m endlessly fascinated by the creative process and have written quite a bit about it here on the site. Turns out, inspiration is lurking in many surprising places.

Local Beauty

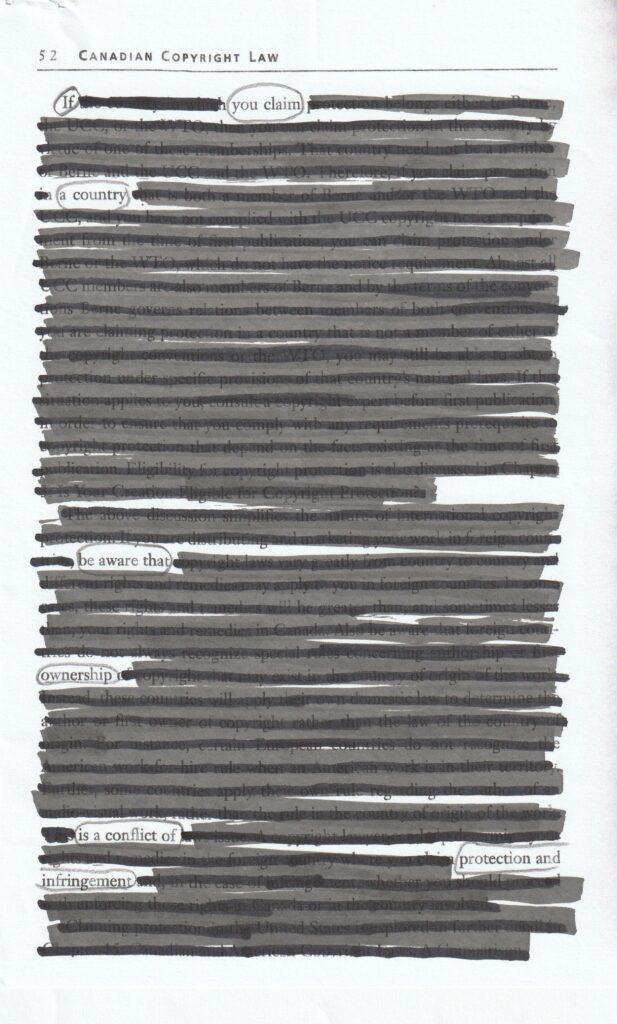

For me, inspiration often lies in the beauty I’ve photographed in my everyday world. Here are some examples of photos I’m currently writing from:

How do I decide which of my hundreds of photos inspire me? When I look at one and think, “now that’s a poem!” Then I’ll start to jot down thoughts about what’s in the picture, what ideas it sparks, what feelings it invokes. The photo is a jumping off point. The resulting poem is rarely a description of what’s in the scene.

Themes and Structures

Another trigger can come from a “call for submission”, where a journal or website announces they are looking for writers to send in new work. Often these calls are for a certain theme to be written about, or certain style of poem to be created. For example, Frontier Poetry recently requested submissions for their “Not in Love Tanka Challenge.” Oh yeah, this is inspiring: to try to stuff such a huge theme into the five-line/31 syllable structure that is the Tanka poem!

I can’t show you that one, as I did submit and can’t publish anywhere else, including here, before hearing back from Frontier Poetry. However, I can show you “White Quill Pen”. This poem was one of three I submitted, answering a call by the League of Canadian Poets. It was selected for Fresh Voices #30. This scene, taken in Canmore, Alberta, inspired the poem. You can see the poem with its photo in my Photo Art Gallery.

Magical Thinking

And yes, sometimes it’s all very “woo-woo” and I’ll wake up with some lines that seem to insist on being written. Recently I got: “Meegwich/thank you, I hope my people were kind.” This led to a poem that is a type of land acknowledgement to the native people of the Niagara Region. My ancestors were some of the very first white settlers there, and the poem includes details from my years of genealogical research.

Your Turn!

So there you go! I hope I’ve answered your question about where inspiration comes from, at least partly. Follow-up questions are most welcome!

Meanwhile, even if you’re not a practicing artist, why not challenge yourself to notice what ignites some excitement, some curiosity, or maybe even an “ah-ha!” moment? You may be surprised by where inspiration comes from. Who knows what may galvanize you… and what that might lead to!

Lee Ann

What Else is New?

Looking for gardening inspiration? Find Seedy Saturday events across Canada in February and March. Shop for low-priced seeds from local sources, talk to local vendors, attend fun and informative workshops. For my Ottawa readers: Look for the Master Gardeners of Ottawa-Carleton’s advice table at the Ottawa event, March 2, 691 Smyth Road, and at the Carp event, March 9, 3790 Carp Road.