THOUGHTS ABOUT HOME ON CANADA DAY

Hello, there!

It’s Canada Day in my part of the world, and that brings me to thoughts about home: what is a home, what home means to me, and also the places I call home.

Do you ever think about that? I wonder how you’d define “home” for yourself.

To me, home is family, and I’m blessed to have a close one: my husband and our boys; my siblings and I; all our children – a.k.a. “The Cousins” – and now the next generation, for whom we’ll have a celebration this month, which has been dubbed the “Dozens of CousinsFest.”

Home to me means sanctuary. It’s the place where I create my definition of beauty: gardens and plants, warm colours inside and out, plus all the special items collected over time and generations.

I’ve realized recently that there are three places I call home:

- Canada. I’m so grateful to my ancestors who chose this magnificent country! I’m currently on a mission to visit the northern, southern, eastern and western-most points in Canada. Two down, two to go!

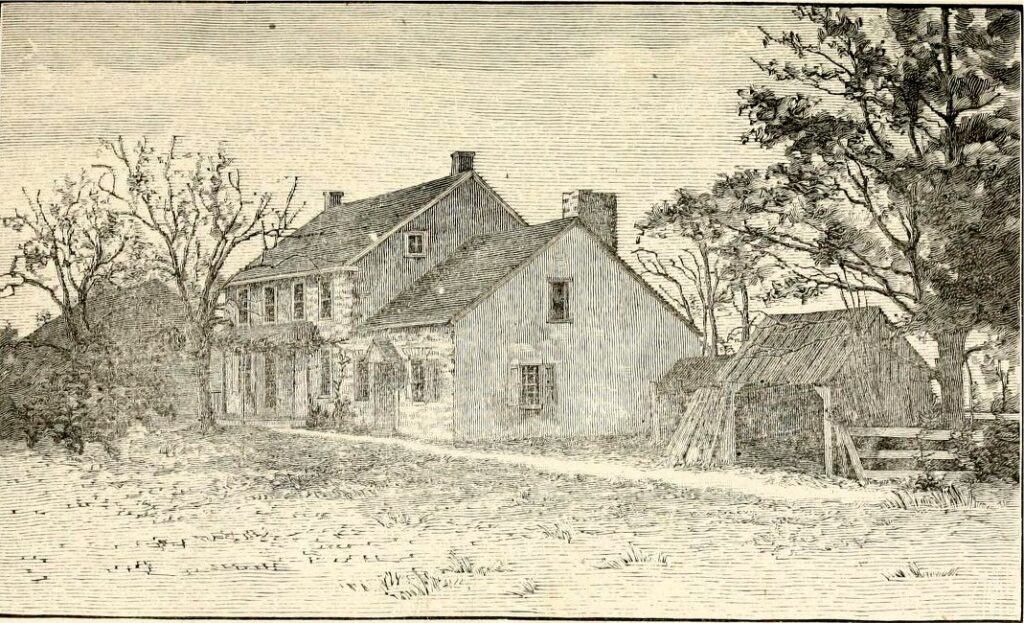

- Richmond and Ottawa, Ontario. My village of Richmond is officially part of Ottawa, yet retains its separate identity and is actually older than the capital. I’ve been out in the village photographing and writing, and the inspiration I’m finding makes this Richmond 200 project so much fun! And recently, Geoff and I enjoyed a “staycation” in Ottawa, taking in the Jazzfest and other activities usually reserved for tourists. We barely got started on the list of things to do and see!

- Muskoka. The Smith family cottage is a magnet for all family members and many friends too. Ten people and 3 dogs are there this weekend, in the middle of a heatwave and a power outage. Still, as my sister is fond of saying, “a bad day at the cottage is better than a good day at home!”

All of this is my long-winded introduction to this month’s photo and poem, called “Where is Home?” Originally inspired by a scene near our cottage, it’s a poem that has had quite a bit of exposure. It was first published in the May 11 issue of the Glebe Report‘s Poetry Corner (page 30); their theme was “home.” You can also see it in the Richmond Hub newspaper, where I paired it with a scene along the Jock River in Richmond, which was no less inspiring to me! I hope you click to take a look at that scene.

Happy Canada Day, everyone! May your thoughts of home be as satisfying as mine.

Lee Ann