FOUND POEMS: Digging for Buried Treasure

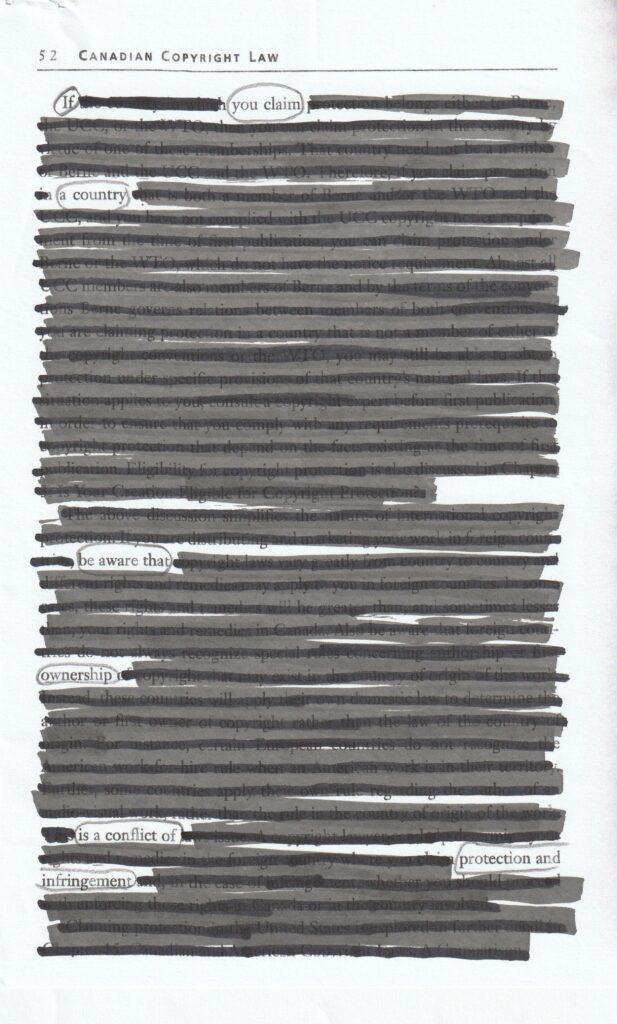

The most fun I’ve had with poetry lately is creating “found poems.” Like a kid with a treasure map, I’ve been mining existing texts for the poetry hidden within. Here’s an example, found of all places in the textbook, Canadian Copyright Law, by Lesley Ellen Harris. I call it, “Advice to Would-Be Colonizers”:

This form of poetry first appeared in the mid-20th Century alongside other types of Pop Art (think Andy Warhol’s 1962 paintings of Campbell’s soup cans). It is art created from recycled items, giving ordinary things new meaning when put within a new context. In other words, it’s finding buried treasure. Newspaper articles, street signs, graffiti, speeches, letters, or even other poems all provide the raw material for found poems. Novels are also a great source! Here’s a poem I found in the classic Mutiny on the Bounty, by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall.

The great event in his life had been an extraordinary affair which broke into an uproar and confusion very strange, far from easy to subdue. Presently the great wave left destruction in its wake leaked into us and it was here that the seeds of discontent, destined to be the ruin, were sown.

So forget Sudoku, forget crossword puzzles, you can exercise your brain by trying this form of poetry! Use the “blackout” approach above, or maybe you’d prefer a literary collage, where the artist (you!) cuts words or phrases out of the raw material, and rearranges them into a found poem. This approach is called “cut-up,” or in French if you want to sound very literary: “découpé”. (Pro tip: don’t try découpé with a library book…)

Remember: poetry is everywhere, often hiding in plain view.

May you find many treasures, buried and otherwise, this holiday season!

Lee Ann

What Else is New?

Any book lovers on your holiday gift-giving list? I can help!

The Other Princess, by Denny S. Bryce. Read my interview with the author and learn about Queen Victoria’s African princess goddaughter, Sarah Forbes Bonetta. This is the latest in my series on Fascinating Women You’ve Never Heard Of.

Growing Joy: The Plant Lovers Guide to Cultivating Happiness (and Plants), by Maria Failla, an enthusiastic how-to book. The ideal reader is someone who is new to gardening, or considers themselves “not a gardener” and who would welcome a light, but informative book. You can read my review on Page 6 of the December issue of Trowel Talk, newsletter of the Master Gardeners of Ottawa-Carleton.