DEEP DIVE INTO MY NORTH AMERICAN FAMILY HISTORY

Seeding a New Country

I recently investigated the whereabouts of my ancestors in 1867 – the year that Canada officially became a country. But the seeds for my country’s formation were actually sown over a hundred years prior to that, when the “Seven Years War” between England and France and their allies came to an end. Key battles in that war were fought in North America, including at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, in Montreal and at Quebec City. These brought about a major turning point for North America and set up the circumstances that would lead to the creation of Canada. They also led to dramatic changes in some of my ancestors’ lives.

Here’s what North America looked like in 1763, at the end of the Seven Years War:

Here’s why that war was a turning point for North America:

- Control switched from France to Britain. After 150 years, France surrendered all its territories to Britain and North America became English. Explains why I don’t speak French!

- French was protected in Quebec. “New France” was gone, and with it the French (Catholic) religion, the French language and French common law – except in Quebec, where Britain made allowances for the French settlers who decided to stay. Canada still struggles with this today.

- First Nations land rights were recognized. The red line shown on the map is where Britain declared the western boundary of its settlements to extend; land to the west of that was acknowledged as “Indian Territory.” This was the first recognition of First Nations’ rights to land and titles. The proclamation did not last; some historians say that what happened to the natives once the Europeans arrived was in fact genocide. And the fallout from ignored and/or disrespected native land treaties established in 1763 is still in the news in Canada today.

And here’s why the Seven Years War is important to my family history:

- I had ancestors living in North America at the time. The “British Colonies” noted on the map were the first settlements of what would become the United States. Thirteen colonies stretching from Georgia to Maine, they had first been established in 1607 and were already British from that time. I had many ancestors, all from my father’s line, living in the 13 Colonies in 1763.

- I had at least one ancestor who fought in the Seven Years War.

My Soldier in the Seven Years War

I know of only one ancestor who was directly involved in fighting in the Seven Years War: my 5-times-great-grandfather Daniel McIntyre. Daniel signed up with the 78th Regiment Frasers Highlanders in Inverness Scotland in 1757, at the age of 21; he was likely a farmer before that. He fought for Britain – in his kilt – at Louisbourg, at Montreal, and at the decisive battle on Quebec’s Plains of Abraham. When the war ended, his regiment consisted of 887 men. Of these, almost half chose to be deployed to other regiments in North America, while others boarded ships back to Scotland. Some settled in Quebec (as many of them spoke French) and some, Daniel included, decided to set up homes in upstate New York or Vermont. Daniel received a land grant of 200 acres in Vermont for his service to Britain.

My Family’s Presence in the 13 Colonies

When Daniel McIntyre settled in Vermont after the war, he unknowingly joined other family members from my father’s line who were already living in the 13 Colonies. Although there were battles fought during the Seven Years War in what would become New York State and Pennsylvania, I have no information that indicates any of these family members from the Colonies were involved:

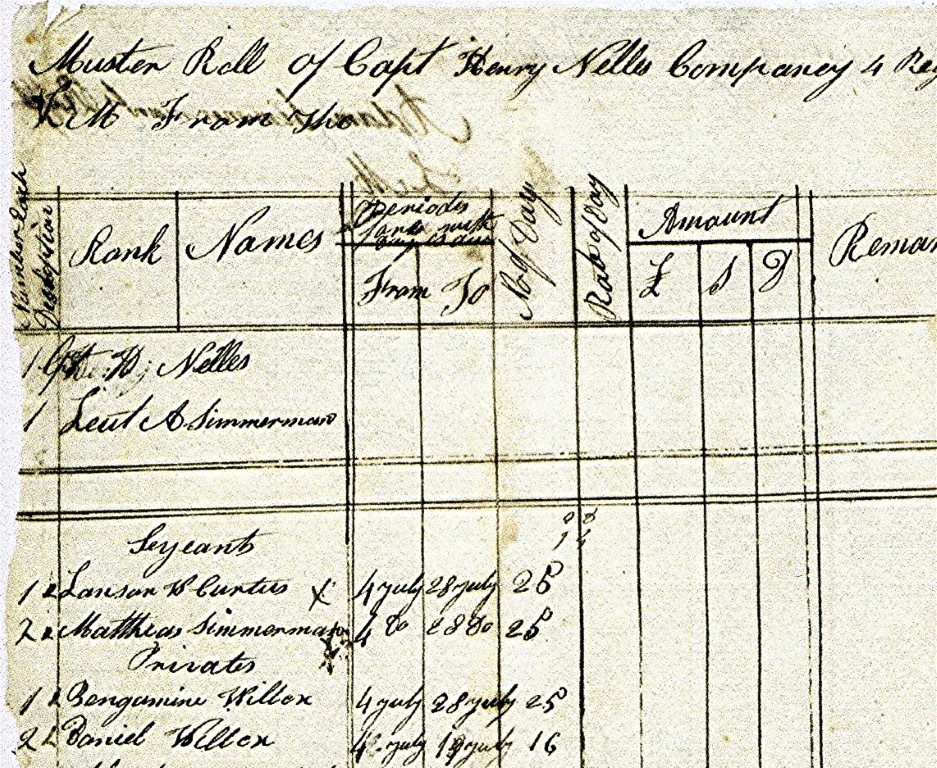

- By 1763, the Wilcox family had been in North America for 130 years! My 10-times-great-grandfather Edward was the first immigrant, from South Elkington, England. He settled in Rhode Island in 1638. At the end of The Seven Years War, his descendant, Benjamin Wilcox, my 5-times-great-grandfather, plus his wife Elsie and daughter Hannah, were living either in Massachusetts where Benjamin was born, or New Jersey, where they moved to at some point.

- “Weaver John” Fretz – so called because he was a weaver as well as a farmer – was head of a large Mennonite family living in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. They farmed together on 230 acres. “Weaver John” had emigrated from Manheim, Germany as a child, somewhere between 1710 and 1720. By 1763 the family consisted of John, his second wife Maria, their eight children and many grandchildren. “Weaver John” was my 7-times-great-grandfather.

- The Boughner family were newcomers to the 13 Colonies, originally from Unnau, Germany. Johann Martin Buchner and Elsa Zehrung had arrived in September 1753, just three years before the war began. They settled with their seven children in New Jersey. Martin was a school master; he and Elsa were my 5-times great-grandparents.

The peace negotiated in 1763 would not last long. Within 12 years a new war would erupt, caused in part by the terms of that 1763 treaty. As a result of the new war, the map of North America would be redrawn again. Daniel McIntyre’s fighting days were not over yet. And many more of my ancestors’ lives would change dramatically.

I’ll continue this story in another post. Meanwhile: what world events have had a direct impact on your family? I’d love to know!