HONOURING PIONEER WOMEN

Hello there! Is it finally springtime in your neighbourhood?

Last week as the air in my neighbourhood finally softened, I took the opportunity to explore Richmond Village – my community. I wanted to see what might remain from its original settlement 200 years ago.

The short answer is: not much remains. The longer answer is that I spent a wonderful few hours along the banks of the Jock River, which bisects the village, in the vicinity of the original “Government Reserve” block of land. Most of this block is now a subdivision, but there remains a small undeveloped piece in the south-east corner. I wandered happily back and forth along a path that used to be where two major roads intersected, delighting in the experience of standing where key events in the history of my village took place. Here in 1818 was the Commissariat, where supplies were handed out and the soldiers collected their pensions. Here was the first school, which for the initial seven years of Richmond’s existence was also home to all denominations of churches.

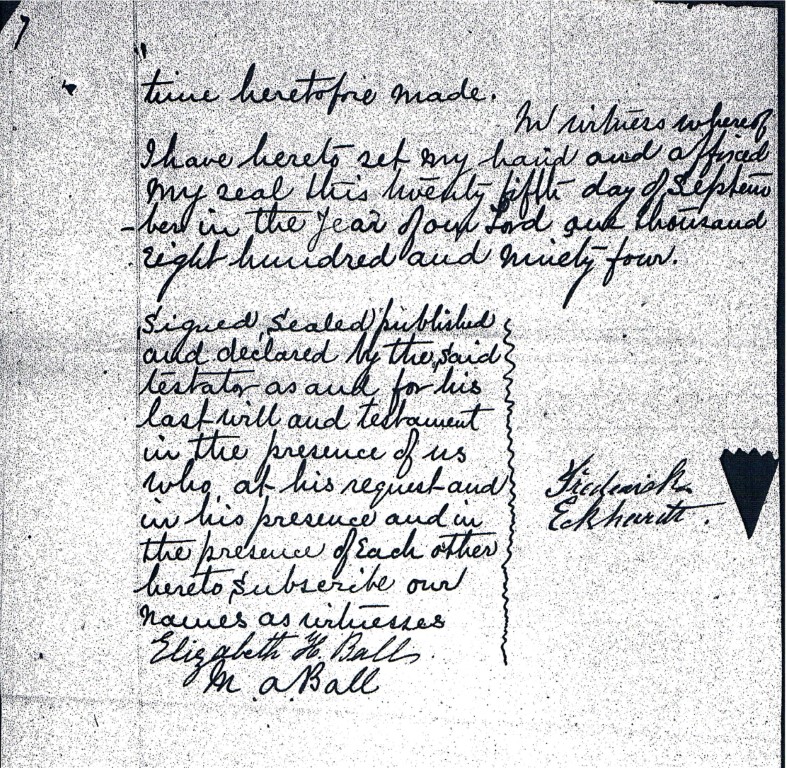

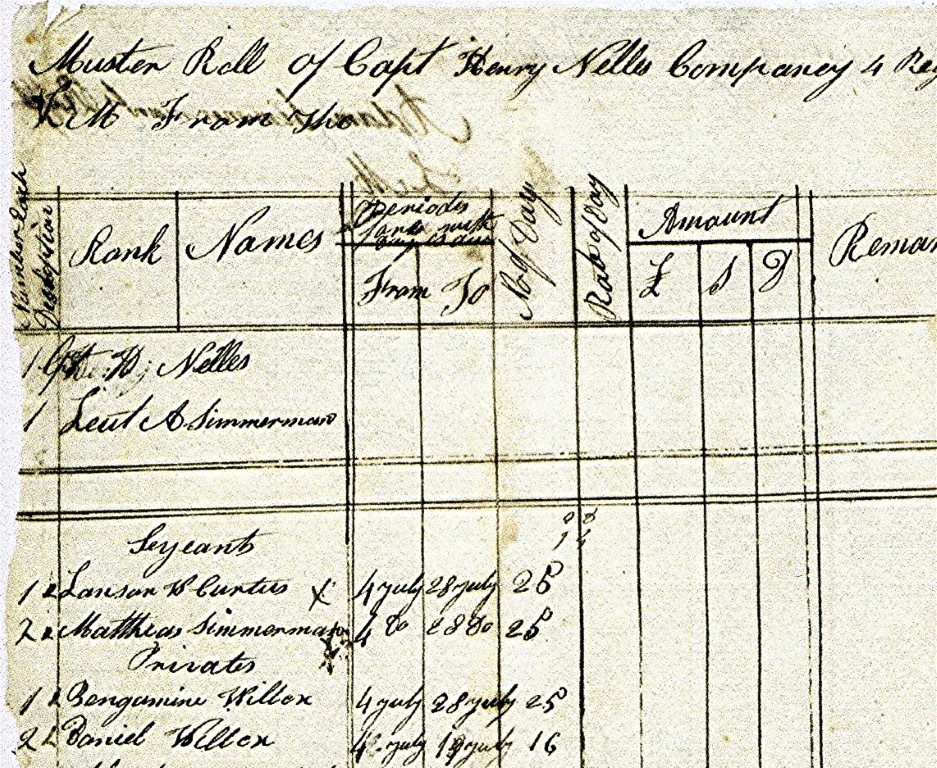

Richmond was a military settlement, established by veterans of the War of 1812, most of them from Ireland. We know quite a lot about the first soldier/settlers: the ranks they held, the businesses they started, the legacies they’ve left in the village, including their names on our streets. As is typical with history, we know much less about Richmond’s first women. I found myself wondering about these women and lamenting how so few details about them survive, compared to their men. I’ve blogged about this topic before (How Women Get Lost in History) and last week I wrote even more about it: a poem based on historical facts, about what a Richmond pioneer woman might have experienced (published in the Richmond Hub).

This in turn led me to think about my own ancestral mothers and how I’ve worked hard to unearth details about their lives that might tell me something substantive about them. For the most part, they remain shrouded in time. This makes me sad, and also makes me want to honour them – especially my pioneer, immigrant great-grandmothers, for the particular hardships they endured.

My way of honouring is writing. So this month’s poem is for Julianna Molnár Gerencsér, my maternal great-grandmother. Happy Mothers Day, to all our ancestral mothers!

Lee Ann