The War of 1812 took up a lot of time in my history classes during middle school. After all, I grew up in Niagara Falls, and much of that war was fought in our neighbourhoods. So every year, my classmates and I were herded into yellow buses and taken down the Niagara Parkway to Fort George and Queenston Heights, the sites of two major battles.

For me, these field trips were beyond boring. I was unimpressed by Fort George’s summer students, the cute, costumed “soldiers” with their pretend rifle drills. From my tween-aged perspective, the statue of General Isaac Brock at Queenston Heights was interesting only because it had once lost its arm and part of its torso in a lightning strike. I stubbornly refused to participate in the annual climb of the narrow, winding staircase inside Brock’s monument. Two hundred and thirty-five steep steps! Plus all the boys said there were bones up there.

Lundy’s Lane in Niagara Falls is the site of what historians agree was the bloodiest battle of the war. This was never a school field trip, since Lundy’s Lane had developed into a strip of fast food outlets and tourist shops, which it still is today. At the Lane’s highest point, Drummond Hill Cemetery holds the remains of soldiers from that battle. My husband remembers finding musket balls there when he was a kid – now, that’s interesting! Too bad I didn’t know about it when I was twelve.

It was only recently I discovered that two of my four-times-great grandfathers fought in the battle of Queenston Heights and also the battle of Lundy’s Lane. And on the opposite side of the spectrum, my Mennonite ancestors refused to fight on religious grounds.

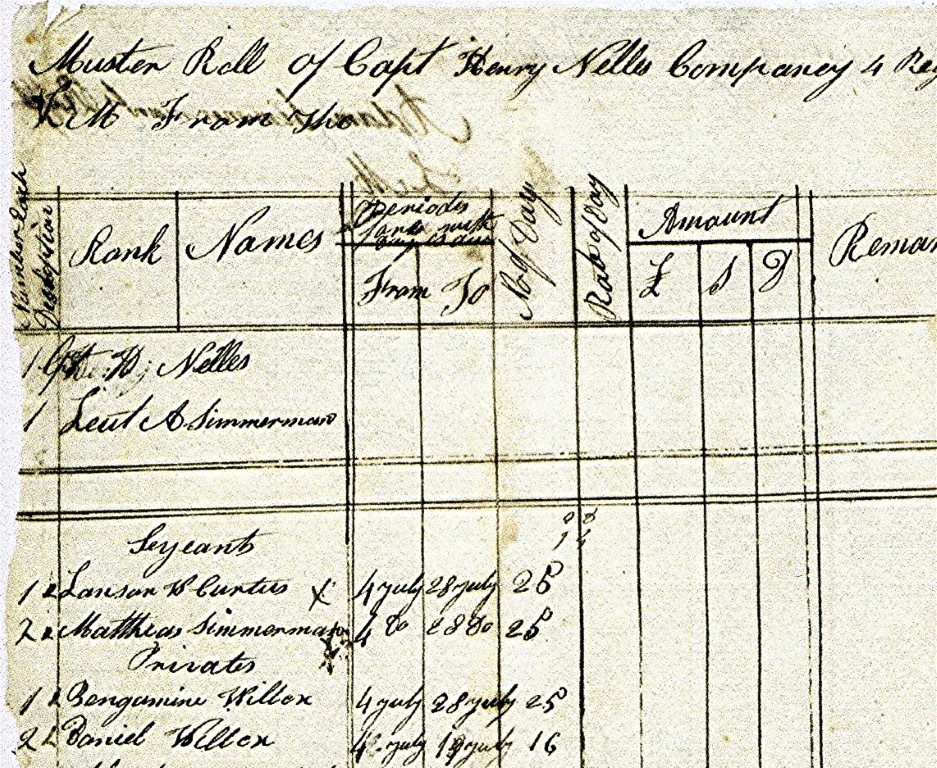

The War of 1812 now feels far more personal than it ever did in history class or on field trips. What I learned opened a window into the life of Benjamin Willcox Jr., who fought alongside his 16-year old son Daniel in the 4th Lincoln Militia. And Martin Boughner, who left a pregnant wife and two-year-old daughter when he walked off the farm and into battle.

The War of 1812 also marked the first test of conscientious objection in Canada. For my Mennonite ancestors – the Honsberger and Fretz families – this test was real, and it was difficult. While exempt from active fighting, Mennonites were conscripted into “non-combatant” roles. This included driving supply wagons to the battlefront, which certainly did not provide exemption from mortal danger. Not to mention the King could “impress” their horses, carriages, and oxen as needed. And Mennonites, like the rest of the Niagara settlers, were not exempt from having army battalions move into their homes and barns and/or steal food from them when the military stores ran low.

One of the things I love most about researching my ancestry is that it transforms history. No longer is the War of 1812 a boring series of field trips, place names and dates. Now it’s a collection of stories alive with real people who belong to me. It’s an event that allows me to reflect on connections and influences that ripple through generations. I’m proud of all my ancestors who played a role in the war of 1812: the men who were called away from farming and families and who possibly had no interest in soldiering; the women and children who had to step up to keep farms operating… and also the men and women who may have stood up against the military, the government and their neighbours, in order to be true to their faith.

**This is an excerpt from my essay, “The War of 1812: It’s Personal,” which was published in Canadian Stories Magazine, Volume 19, Number 111 (October-November 2016.) You can order a copy of it here.