PROGRESS REPORT

Writers live and die by word counts. Everything is measured by number of words: how big is this book? What is the magazine’s preferred article length? How many words to I need to write per day to get me to the 20-30 pages (5,000 to 7,500 words) required by City of Ottawa Arts Funding Program by January 15?

Since returning from the Ontario Archives I’ve held myself to a target of 4 hours or 500 words(whichever comes first), 5 days a week. Sometimes this schedule feels a bit relentless, but overall I have to admit that it is quite comfortable. And the words add up, even though some days I don’t produce the quota because I spend all 4 hours researching.

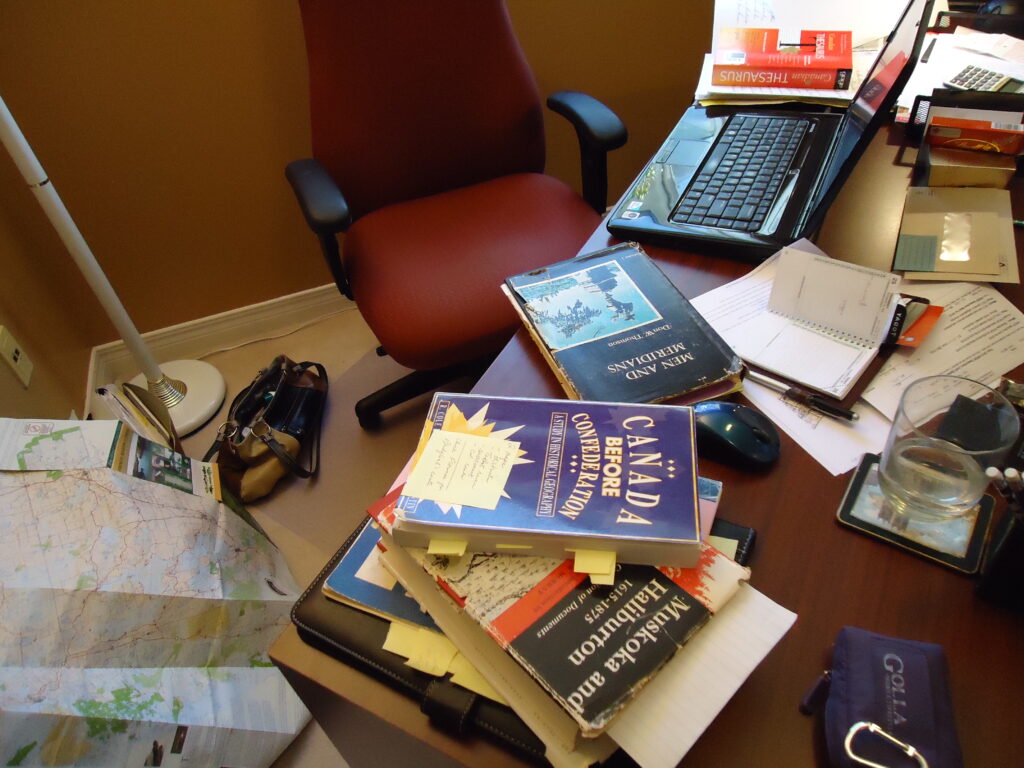

I’m sitting at about 6,490 words now. That’s 20 double-spaced pages. This is what my process looks like:

1. I read over everything I have about a topic, then I write about it. I stuff my head full of information, say on Dennis’ 1860 survey, then I wander around the house thinking, what am I going to say about this? For awhile the answer is, “I don’t have a clue,” but then I take my own advice from the workshops I teach and pretend I’m telling the story out loud to my best friend: “Have I got a story for you!”

2. I write what I feel like writing. From my outline, I know the overall shape of this book: a chronological narrative of the road, from the first surveys to its current existence as part of Highway 11. Eventually I’ll write the whole story. But I started with the surveyors, because I was most interested in them, and I have great primary source material – their diaries and field notes – and because the 19th century is my favourite historical time period. But I’m already feeling the need to pull up from the detail and write an overview of the district. I’m also getting keen to focus on the settlers: who were they, how did they get here and how did the free grant lands work? If I write what I’m keen to write, the writing should be lively because my enthusiasm should show up on the page.

3. I create little “quilt pieces” of text that I sew together in a separate step. I tend to pick a topic and write a self-contained piece about that and worry about how it’s going to fit into the narrative later. This is something my writer friend Joan taught me years ago: writing is like quilting, where you first make these little squares, then you sew them all together later. So I have a number of quilt pieces so far, like: profiles of the surveyors and how they were connected, first-hand accounts of what the road was like in 1860-61, and a description of early Washago, where the road begins. (They kept some of the rattlesnakes in cages. Really.)

I did set out wanting to take more of a tortoise than a hare approach to this book. So far so good! Nothing yet has flipped me on my back and left me with my feet waving in the air.